A number of year ago I had the great fortune that a film that I conceived of, wrote the treatment for, and ended up co-producing got made and had two theatrical releases. The film had its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival (and won a commendation there), showed at the UN four times and I ended up touring with the film for some time going to screenings, festivals, schools, and the like about the subject of the film ‘why does poverty persist in a world with so much wealth? Why does it increase in fundamental ways when so much effort is put towards reducing it?” The film “The End of Poverty?: Think Again” asks big structural questions with no simple ‘bad guy’ to point at.

When I was on tour the question that came up from audiences the most wherever I went was ‘What can I do? This subject is so big?’ I didn’t have a standard answer for the question but broadly my response was “we need you to start where you are and do what you can. If you work at the World Bank – we need you to know about this and work from there. If you are an activist and you are inclined to protest the World Bank, we need you too. If you are a single mother who has little bandwidth beyond gardening your little plot, sending a few dollars somewhere and recycling…we need you too. To know about these big issues and how your efforts point towards working on them.”

In recent days all over the United States there have been protests alongside and interwoven with the Black Lives Matter movement and around the death of George Floyd specifically regarding ‘Defund The Police.”

This policy idea, for some, is a thrilling clean-burning fire – ‘it’s about time this is discussed and lets go further while we are at it’ moment. For others it is moment of policy thick with gritty nuance – “defund the police means right sizing it and taking bloated and ineffective police budgets and applying those dollars to underfunded spaces and having newly and well-trained police respond only where required and having social workers respond to family issues and disputes and specific experts responding to issues that arise rather than automatically policing issues.” And for many others it is a terrifying and ridiculous prospect to ‘defund the police’ and imagining what sort of lawless and anarchic streets are to befall us is a grim shadowscape to be avoided at all cost and measure. I don’t know where you fall on this spectrum. Or off of it.

Regardless of your thoughts and feelings on the matter there is a sense that the threads of the order we have known around law enforcement are being unraveled. Or maybe tugged at and many are yearning to re-weave a new textile instead of the one we have. But it is hard to imagine something that we have never seen or experienced.

Broadly speaking the system of justice we live with and within is called “retributive justice” which emphasizes justice through punishment of the person or persons who violated some law or laws. That punishment could be monetary in the form of a fine or restitutions towards the victim or it could be carceral in form of varying levels of confinement, containment, or jail. This form of justice does not emphasize rehabilitation. And while it is not necessarily easy – trials can go on for years, corruption abounds, racism impacts outcomes and myriad other impediments the system is driven to the gavel banging resolution – guilty or not guilty.

This binary end does not always feel like resolution though and often doesn’t feel like justice either for many involved in the process. But it is what we have and the crime and the criminals keep on coming with each update of the penal code.

In 1974 in Elmira, Ontario, Canada an ancient approach to justice began to intersect with the modern carceral approach. Two young men were found guilty of stealing from and ransacking twenty two homes. The defendants were found guilty but before sentencing the volunteer Mennonite probation officers who were assigned to the case petitioned the judge to allow them to try a kind of reconciliation that was ultimately accepted. These two young men, teenagers, were compelled to meet each of their victims and have varying kinds of dialogues with them and make the kind of restitution that each party wished for. That was money in some case and expression of feelings in others. In the end all twenty two victims said they felt satisfied with the outcome. This was considered a success by all accounts. The guilty parties were kept from going to jail, no court resources were unduly strained, the victims felt satisfied and the community that was stolen from which was also where the young men were from was more closely knit because of all the group dialoguing they had to do.

This was a successful case but deeply improvised by good case workers and largely unskilled. Regardless they started to expand their work and ended up intersecting with many indigenous groups in Canada who had been practicing similar methods in their own communities of what became known as ‘restorative justice’ or sometimes ‘transformative justice’ and also sometimes ‘indigenous justice.’ These members of the formal legal and judicial branch of law enforcement started getting trained by indigenous people to implement their techniques in all kinds of cases from petty crime all the way to issues as serious violent crimes. It obviously doesn’t suit all cases and the parties involved have to consent to this kind of action -if it is available where they are. But the outcomes have been remarkable and indigenous communities in Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand have led the way to reimagining this part of the criminal justice path and how policing happens and heads towards.

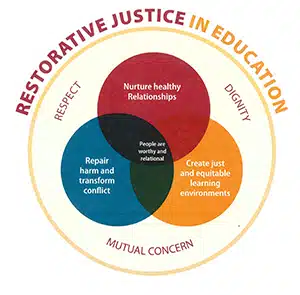

Broadly here are some of the principles that apply:

- Crime is understood as harm against the entire community, affecting everyone.

- Elders are in a leadership role in the resolution process, and the whole community explores their role in the incident and in the needed resolution.

- No one is disposable….so the offender needs to be cared for, and re-integrated back into the community, not driven out in shame. The needs of the victim are also crucial to the process.

- Healing circles express and integrate native traditions and spirituality.

- Healing circles allow all participants to speak about how the incident has affected them.

- Healing circles empower the community to handle wrongdoing themselves.

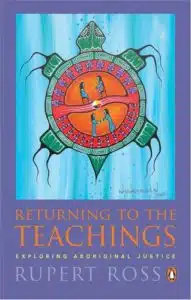

Perhaps the ur-text on the subject is “Returning To The Teachings” by Rupert Ross which has dozens of case stories and tells the story more fully of how Canadian indigenous people shaped this emerging legal resource from their own cultural traditions. I highly recommend it.

But restorative justice is not easy. It takes time and its outcomes are not sure and are outside of standard timelines. It is what you might call ‘labor-rich’ to do well. But if that is a price for a more finely knit together community may such a thing be stitched.

When I spoke to the viewers of my film in the talk backs about how they were needed to do their work on poverty from wherever they were with whatever they were inclined towards I think that it applies to this elusive question of policing now. You might not be inclined to march in the streets. Maybe you are overwhelmed with the choices of books and movies about anti-racism or black history. But maybe you are committed in small ways to improving the connections between your neighbors to have a more connected and resilient community. If that is your natural inclination then maybe we need you to learn about restorative justice and how that is part of visioning policing in a new way by learning about these old pathways.

So perhaps find a copy of ‘Returning To The Teaching” by Rupert Ross or go poke around at Living Justice Press which is a non-profit publisher that only deals with books about restorative justice. Maybe those books or trainings are your way in now to responding to this moment. If you need help choosing which book might resonate with you, reach out and I’ll help.

There is much to say about restorative justice. I have read about it widely. Attended some trainings in it and watched parts of reconciliations in process as a guest. It has moved me to prayer and weeping and awe on more than one occasion. But I write about it today for two reasons. One is that I am trying to make these newsletters faithful to the times we are in at the moment and not to simply just gloss over these unfolding times. Policing is now more than even in the news, it is in the contemplative psyche of the nation. I can’t skip that. But the second reason is that Primal Derma is also not easy to make and is a labor rich endeavor that has unsure outcomes. These virtues are ones we value here on this end of the world. Where you can find the thumbprint of human work and the mystery of outcome while walking an old path that might draw a community a bit more closely together to tend to hard times… then we are in.

As always, thank you for reading and supporting Primal Derma with your purchases and your emails back to me.