Vasco de Gama the famed Portuguese explorer and leading edge for European imperialism in Africa and India and Asia landed in India in 1498. Once this trip was finally deemed possible and actually profitable this opened up the viability for the main European powers at the time to start to trade primarily tea, spices, textiles (silk, cotton, indigo), and opium. But many other things became commodities as well, jewels and precious stones to name two. While smaller individual traders had made their way, The British East India Company was formed in 1599 to be the main pathway for these goods from India to make their way to England and any number of places after that.

By 1757 The British East India Company had grown quite large but had other imperial competitors in northern India, notably France. At the Battle of Palashi in that same year the British East India Company moved from being a trading company towards being a ruling power. With their own armies of more than 260,000 men and hired guns they drove out the French and the local rulers in the Bengal region and installed puppet governments of locals who were loyal to the business interests of the British East India Company and suddenly, and very quickly, most of India was under British East India Company control. The power of the company grew until 1857 when the company was dissolved and Britain herself formally became the ruler of India but still employing all the same political gambits to extract maximum wealth from the country. The Indians were not happy about this – to put it mildly.

The word ‘thug’ has been in the news lately. Police are calling protestors ‘thugs’ and looters are being called protestors when they aren’t always the same. As the debate about what will policing in the United States look like going forward after the cruel killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis the latest of too many deaths that came about in similar circumstances all over the country. The death of Breonna Taylor is also feeding the grief and the protests as well. Many, wrongly and with wrenching racism, have tried to malign George Floyd and Tamir Rice and Ahmaud Aubrey and Philando Castile and Sandra Bland and Freddy Gray and Trayvon Martin and Eric Garner and so many others as ‘thugs’ as some kind of justification for their murders.

Thug. As all this unfolds the word ‘thug’ comes up again and again. The term has been used as a largely racist cudgel towards black and brown youth who have done their best to try and reclaim the word – there are nearly 5000 songs in the entirety of the English speaking hip hop/rap corpus that have the word ‘thug’ in the title. But often ‘thug’ is a title cast upon black and brown people preemptively and presumptively. The reality of this is that these people are often criminalized just for existing before ever doing anything.

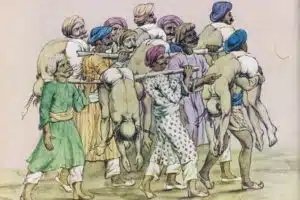

If you look up ‘thug’ in the dictionary you find “a violent person, especially a criminal.” And if you look up the etymology you’ll see that the word is both Hindi and Urdu word ‘thag’ (pronounced more like ‘tug’ with an aspirated ‘t’) and this little piece of history is tossed in as a bit of interesting color… “a member of a religious organization of robbers and assassins in India. Devotees of the goddess Kali, the Thugs waylaid and strangled their victims, usually travelers, in a ritually prescribed manner. They were suppressed by the British in the 1830s. The act and the group itself was called ‘thuggee.'”

In the 1830’s in India there was an officer of the British East India Company named William H Sleeman who became the expert on ‘thuggee’ with the publication of his book ‘Ramaseeama’ and vowed to eradicate this practice and all who engaged in it. And over a decade Sleeman was almost solely devoted to finding these ‘thugs’ and their support systems while promoting his successes. He had thousands arrested and thousands executed for their crimes of being ‘thugee.’

The word ‘thag’ was used as far back as the medieval period of India where it could range in meaning from petty thief to murderer but also for a simply selfish person. But there was little sense that this was a long standing group or secret cult. The British East India Company first started to deal with random ‘thuggee’ acts in 1807 and 1809 but it was a political and trade issue rather than a moral crusade. Small caravans of wealthy traders or BEIC wares were sacked and a few people killed. But it was intermittent even by the BEIC records. The records kept on this are thin and one sided but it seems that even Sleeman’s own records are highly contradictory and racist with a kind of imperial paternalism laced into them but seemingly more of these events started happening in 1829 which charged Sleeman up. Sleeman seemed to emphasize up the pointless Indian-on-Indian bloodshed as a fault of the ignorant religion as a way to gain favor with the evangelical clergy. That said, even the Indian-on-Indian bloodshed seemed to be rare and killings of, or theft from people involved with the British East India Company were more common. These ‘thugs’ were much more likely anti-colonialists than a religious cult. Sleeman used paid informants and started to leverage local disputes into him becoming the expert on all things ‘thuggee.’

Because of Sleeman’s power of self-promotion the notion of the Indian thug took off and became part of regular English usage and his likely fabrications and misunderstandings of local culture and local resistance became part of the lore that is even kept in modern dictionaries.

There is a lot of modern scholarship on this and this is only a summary but it captures, I think, the nature of the disputes which are present with taking Sleeman’s history as the sole one. But it is heartbreaking to see that the word in its colonial function is echoing again. What Sleeman did to Indians with ‘thuggee’ the United States police state did to black and brown youth with the very same word. Titled them, profiled them, had them turn on each other, paternally placed themselves as knowing better and that the thugs couldn’t do better themselves. All while not understanding how their very presence and manner of treatment was likely inducing the very behavior they were trying to control and root out. The word, not understood contextually to the culture, easily slipped from England to the US and by the 1860’s it was ensconced in America with similar connotations as we have it today and was used as a racist bludgeon.

So I write today not to extol the virtue of the ancient tradition of ‘thuggee’ as something we should remember and know about and take heart with as I have done before in other epistles to you. But knowing that ‘thuggee’ might well have been very likely to be pockets of resistance to oppression might change our understanding of its current usage. Maybe you’ll hesitate in how or who you use the term for now knowing more about its history. Perhaps not. But even more specifically I write today because here at Primal Derma we strive to put stories into cultural context so they can be reckoned with more fully and with their complexities. Our tallow comes from animals that die, grown by farmers who are trying to work against an industrial meat production system that destroys the earth. This is complicated and nuanced. Grow things so they can die so that other things can live? All deaths aren’t the same.

There are other skincare producers that use tallow (but not many) who praise cows and the efficacy of tallow but skip over the nuances and paradoxes and proper contradictions that stop our tongues. Primal Derma isn’t superior to these other companies. I don’t fault them. This is a hard thing to do to contend with – history, culture making, animism, and much more. But over from my side of the newsletter trying to keep this venture alive it seems to me only proper for me to struggle with such things as I bring you these little jars.

Blessings to your well walked floors maybe getting a bit of mercy soon.

Matthew