The earliest examples of art we have in the world are either simple human figures, simple geometric patterns, hand prints, and human/animal hybrid sculptures. Or animals. The oldest painted art we have found in Europe comes from Southwestern France. The famed cave art from Lascaux and other caves are a wonder and about 20,000 years old.

People have been looking at wondering about animals in the Southwest of France for a long time indeed. To suppose that these ancestors simply looked at the horses or giant cats or bison or birds that they depicted on cave walls as simply potential meat or skins for clothing is to project our sense of modern utility onto the imagination of the ancient people. Animals were signs and evidence and heralds and messages of a thrumming world. These animals had a magical, oracular, and sometimes sacrificial functions that needed a cultivation of a kind of deeply seeing and radical eye from people to participate in the world at all. Radical in the sense of a deep root of a something. To have that eye for animals meant to be rooted to the blue green world.

Even the fairytales and myths of the west which are, roughly as a group, about five thousand years old, have talking animals and the rare exceptional beings who could speak with animals in their language or speak to them at all. This is tracking a memory that there was a time that people and animals had a more intact relationship that might have been degrading even five millennia ago.

In the last two hundred years animals have left our sphere by and large. Pets and zoos and the spectacle of ‘the wild’ are what we are left with. With the exception of maybe stuffed animals that we festoon children with. And so there might still be a longing for seeing animals.

If your ancestors are from the Southwest of France, maybe near the Bay of Biscay or inland from there in the area called Les Landes is now a pine forest that started to be planted about 100 years ago to make the land more ‘usable.’ That planting changed the soil and quickly ended sheepherding and a maybe millennia old tradition. For a very long time before that planting was something that we might call moors or heath. The name Les Landes means ‘heathland.’ It was a semi-marshy soft soiled kind of a place that was great for sheep. And all signs point to sheep having lived there for thousands of years.

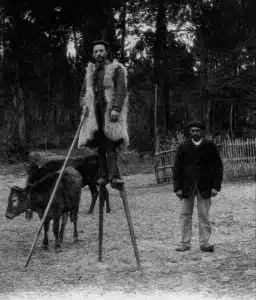

While the heath was great for sheep it wasn’t easy for humans who lived with the sheep to get around on the soft and often wet ground. And so the sheepherders from Les Landes devised stilts to more easily get around and watch the herds. These stilts were made of wood and about five feet high or so and traditionally the foot of the stilt was secured and strengthened with the ankle bone of a sheep. All so that they might see these animals and care for them better. The stilts called ‘tchangues’ meaning ‘big legs’ in the local dialect were so effective that they became fairly standard for people in general in the region. You know, to just wear around…doing regular stuff.

The shepherds had a long crook which they used to get up on the stilts and also to tend to the sheep but more importantly these stilts were an expression of a deep culture of being in touch with the place and the need to see animals in a profound way. The shepherds of Les Landes may not have had exactly the same magical and ancestral oracular relationship as the residents of the same area 20,000 years before but using the sheep ankle bone as the reinforcing ankle of their stilts is a distant memory that there was a relationship that meant their lives were braided and plaited together and expressed as an artful way of life and of proceeding.

Here at Primal Derma we seek to remind you of these old and deep traditions of culture that have bound peoples to land, to place, and to the animals that lived there. How the eyes of these ancestors have been trained to see beyond utility to cultivate relations with these places and all the inhabitants there.

We, here in what is called ‘The West’, are largely bereft of the eyes to see deeply a relationship with the non-human world and yet there might be a fragment of a memory that you inherited even if you didn’t experience it yourself. And you don’t need to have ancestors from Les Landes to know such a thing.

With any fortune using Primal Derma and reading these stories invites you to try to remember such a relationship and look for signs in your corner of the world while learning about the histories of these cultures and bringing a bit of the animal world back towards your hands.

Thanks so much for your ongoing support of Primal Derma and our wonderings on culture and maybe reclaiming it while tending to your skin.