Somewhere along the road of your learnings you may have picked up the piece of trivia that glass is a liquid and not a solid. And maybe you read about crazed glass and how churches with windows that are hundreds and hundreds of years older are thicker at the bottom due to the slowly flowing glass as it patiently submits to gravity. The down and dirty of the tetrahedral chemistry isn’t really required but suffice to say that it still isn’t certain The flows of glass are theorized but telescope lenses that are 200 years old still work perfectly and flows would distort the optics. But glass isn’t totally solid either. Glass is categorized as an ‘amorphous solid’ or ‘highly viscous liquid.’ This is a point of discussion/contention among material scientists and I’m not certain what the answer will reveal in the end…if there is an end. Regardless of that, certainly you’ve seen glass blown and coiled and made into all manner of color and shapes on a weeknd PBS show or at art fairs or in color plates in books that capture those carboned orange blobs ballooned into forms. The function of glass in our world is overwhelming ranging from drinking vessels to fiber optic cable. It is kind of a magical substance made from silica. So magical that it is neither liquid nor solid.

Glass, despite being a partial mystery to material scientists, is stable enough for it to be tremendously useful and flexible in its applications. But while it seems to be stable, glass is actually a metastable material. More mystery and inbetweening from glass! A bowling pin is an example of an object that is metastable – it is stable in its form/position but a little bit of force on it and it shifts position into an even easier state for it to hold. In the case of the bowling pin…it’ll be on its side which is a more stable position than upright. In the case of a diamond, another metastable material, if it became stable by a flip of some magic switch every peak crown jewel would turn into a chunk of graphite. That same switch would make all glass turn opaque and collapse into a block of silica. Martensite, a critical component of steel is also metastable. Metastability, in no small way, holds up our built world. Wood is metastable! It is a funny thing that in such uncertain times that we seek stability but in many ways we rely on metastability without even knowing about it.

While natural glass like obsidian (from volcanoes) and impactite (from meteorites impacting sand) have been the hands of people for a very long time, the capacity to make glass came to pass about 6000 years ago in either Sumeria or Egypt – it’s not clear who did it first. Either way for about 4000 years the technique for forming glass vessels was about the same – coil molten glass around a form made of a mixture of clay and animal dung and let it cool.

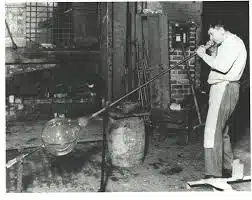

About 2000 years ago, on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea, where the Phoenicians worked and resided, a new technique was tried and mastered that changed the art of glass work – the blowpipe. Using the blowpipe, glass could be made thinner and moved into new shapes that were impossible with the older technique. The sand in that part of the world also happened to be very high in silica which made for excellent glass as well. This blowpipe technique became the standard around the world and perfected in places like Murano, Italy with their gossamer beads and vases. And also into industry where machine blowpipes made lightbulbs by the millions millenia later.

But also about 2000 years ago in a town called Sarafand on that eastern edge of the Mediterranean a glass forge was built and parts of it still stand today. That forge is run by the Khalifeh family and they have been making glass there for a very very very long time in the traditional way.

I write about the Khalifeh family and this ancient art and the ancient forge because Sarafand is just south of Beirut, Lebanon which had a massive explosion there this week in the Port of Beirut where 2700 tons of ammonia nitrate ignited killing 150 people and causing massive damage. While all sorts of accusations were hurled towards all kinds of regional actors, at this point it seems as if a fire caused the explosion. Lebanon is not a country without troubles but so often when we think of that part of the world, or of Lebanon in particular, we think of violence. But this is not the beating heart of that land. In Lebanon a real and true culture was birthed. And maybe it was only there, with those people in that place could have been the ones who learned to manage to muster magic from its perfect sand for 2000 years and find a way to keep on making glass in a slow and handmade way despite the fact that industrial glass is churned out hundreds of times faster and is much cheaper. The Khalifeh family now recycles glass and makes new pieces in their ancient forge to keep their devotions to the craft and to their ancestors and their ancestors to come well remembered and well honored.

These sorts of skills and hand crafts of hewing to the old ways despite all odds are ones we align with here at Primal Derma. These magical transformations of material into one of use and beauty that still has the thumbprint of human work in them is just our speed. We try to do the same with our tallow. Supporting these pathways are the ones that, in our estimation, are the ones that are most needed in a time like the one we find ourselves in. Not to replicate the past mindlessly but to traverse with these ancient gifts with a head down towards an ever retreating horizon seeing how these gifts alter our capacity for seeing.

I pray you’ll take four minutes and watch the Khalifeh family do their work in this ancient way. You can also find them on Facebook and support them there.

Thanks so much for your ongoing support of Primal Derma and our telling of these sorts of good people and their work in the cultured world.

Talk soon enough,

Matt